The sunset of the ticker tape parade

The Army and how Americans study and apply history. Part II.

In his book The Arc of a Covenant, Walter Russell Meade writes about the Planet Vulcan theory that captivated astronomers at the end of the 19th century.1 Puzzled by his inability to reconcile Mercury’s orbit with Newton’s Laws of Motion, French astronomer Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier—who accurately predicted the existence of the planet Neptune—argued there must be a smaller planet somewhere between Mercury and the Sun: Planet Vulcan. The theory was wrong—it would finally be put to bed with Einstein’s Theory of Relativity—but it illustrates the appeal of simple solutions to complex questions.

When talking about changes to the U.S. Army and the field of history in the latter half of the twentieth century, our challenge is not debunking some mysterious force, but rather making sense out of the bewildering array of explosive and highly-visible forces that played out across America. For some, the Vietnam War, in particular its impacts on the Army and society is the main story; for others its the array of social and civil rights movements that gained prominence during this period; or its the changes new technologies and shifts in the economy wrought on the social fabric. That each of these developments, and many others, influenced both the Army and the field of history is beyond question, but to over-index on any one risks creating our own Planet Vulcan.

Further complicating our task is the fact that the period of time under analysis, the late 1960s to the close of the 20th century, is “felt history” for Americans in 2025. Many of the issues which animate our politics today trace their roots to this period and our contemporary ideological perspectives often flow from how we understand the changes America experienced during this period. This increases the risk of analyzing historical events through today’s ideological lenses and frames.

So rather than make any sweeping claims about this period, I synthesized a range of research and writing to put forward three arguments: first, that the field of history grew more fractured; second, that the Army moved from being a driving force in shaping the field to serving as a supporting player; and third, that both the Army and the field of history grew more professional and specialized.2 If we were to think about history as a marketplace, the net effect is that by the end the 20th century, while the size of the market had grown (i.e, more Americans than ever were consuming historical products), it was more fragmented and the dominant players were increasingly games, movies/television, websites, and non-academic historians.

One way to picture the shift is to consider New York City’s Canyon of Heroes. This is the series of plaques along Broadway commemorating every ticker tape parade held in the city. The first parade was in 1886 to honor the Statue of Liberty and the most recent one was in 2024 to honor the WNBA champions, the New York Liberty. But the golden era for ticker tape parades was 1945-1965 when, as the Downtown Alliance puts it, “The city perfected the art of an efficient ticker-tape parade”. During these years the city staged 130 parades (62% of the total thus far).

1969 parade for the Apollo 11 crew. Source: DVIDS.

After 1965, however, the parade fell out of favor. They were held so infrequently that between 1966 and 2024, the Canyon added only 28 plaques. The causes for this were myriad, but it's hard not to see in this a fracturing, a stepping back from common experience and story, and a more critical stance towards themes which in earlier days had been thought of as conventional or traditional.

So it was with the field of history as well. During the period of 1945-1965 the field was growing in size and gaining in prominence, and the emphasis was on common experiences and national history. This is not to say history was not contentious or debated intensely; Americans have always argued over history—the history of the nation’s founding was immediately fought over by partisan news outlets in the 18th and 19th century, for example, and for centuries institutions such as the black press regularly punctured traditional narratives about race and history. With that said, the post World War II decades were a time of convergence, when the same stories, myths, and markers of history were understood in similar ways by large proportions of the population. This convergence made it easier to hold parades as organizers could predict with greater confidence high turnout and excitement. But as the nation and the field of history shifted into an “Age of Fracture” (to use Daniel Rodger’s term), fewer and fewer parades made their way up Broadway.

Two Big Things

The first step in understanding this period of time is to acknowledge two massive shifts that occurred in the 1970s and 1980s. The first, as shown in the chart below, is that the field of history underwent a dramatic and sustained decline in terms of popularity with US college students. More than six percent of bachelor degrees among men in the late 1960s were in history, but by 1985 the comparable figure was two percent. The same pattern held for women as well.

Source: The History BA since the Great Recession

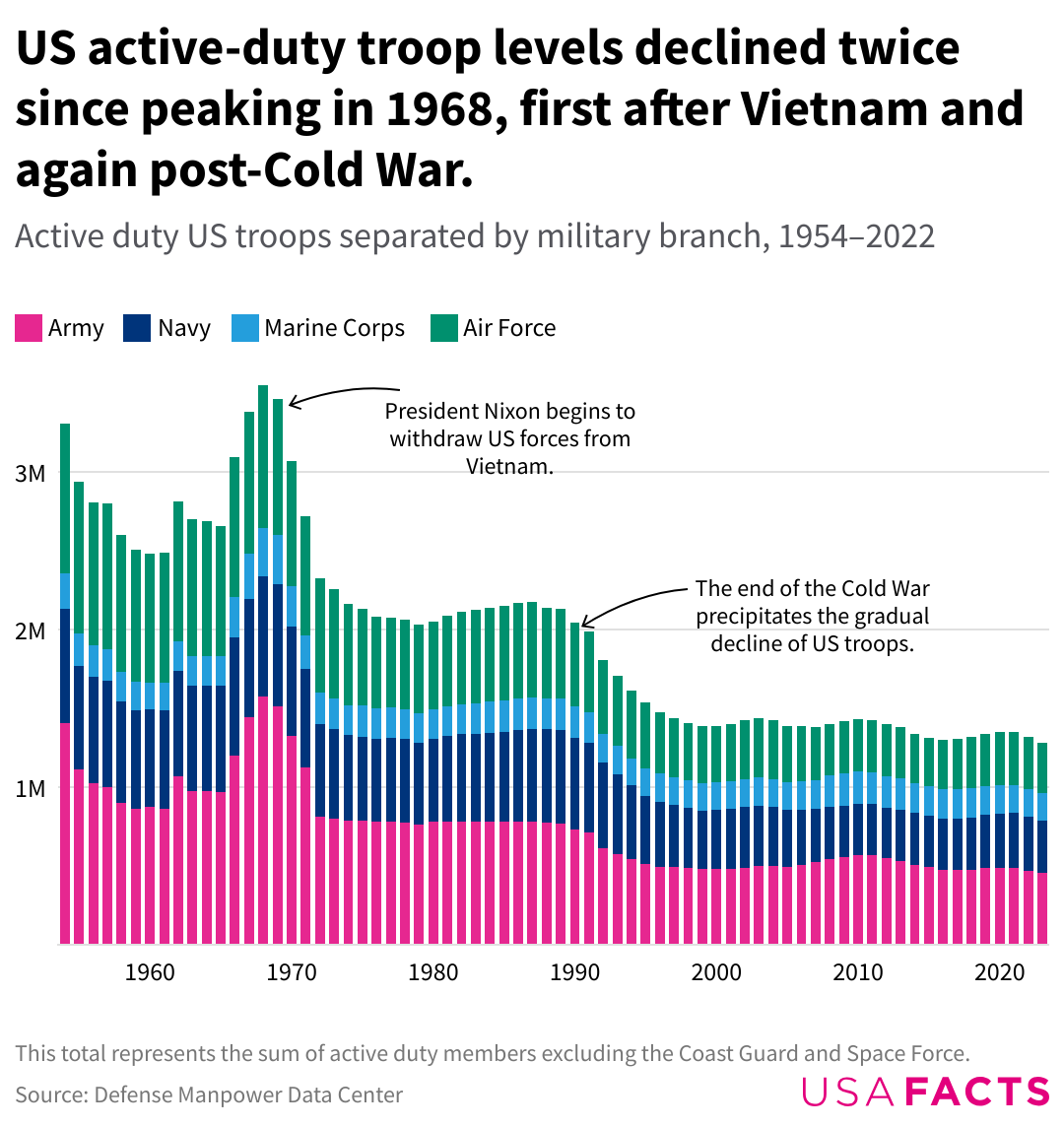

The second major shift is that the Army, as a feature in American society, grew significantly smaller. As shown in the figure below, after peaking at an active duty strength of approximately 1.6 million in 1968, the Army shrunk to below 500,000 in 1996. There were similar changes in terms of the veteran population and the number of domestic bases; as a consequence, the Army became more distant from much of American society.

Source: USAFACTS.

The confluence of these two shifts gives credence to the idea that many Americans lost interest in both history and the Army. This was the “End of History” period after all. But this is not the full picture. To see this, we have to dive into smaller changes that played out within the field of history and the Army.

Changes Within the Change

Historian Jill Lepore, in her book This America: The Case For The Nation, describes the changes to the history profession that begun in earnest in the late 1960s and early 1970s.3

“In the 1970s, the historical profession broadened; so did American history. Studying the nation fell out of favor. Instead, most academic historians looked at either smaller or bigger things, investigating groups—divided by race, sex, or class—or taking the vantage promised by global history. They produced excellent scholarship, meticulously researched and brilliantly argued accounts of the lives and struggles and triumphs of Americans that earlier generations of historians had ignored. They studied people within nations and ties across nations. And, appalled by nationalism, they disavowed national history, as nationalism’s handmaiden.”

Historians Hal Brands and Francis Gavin make the case that the changes Lepore describes, at least initially, had an acute impact on the study of military history, with both students and universities shifting away from courses that emphasized war or the military. Instead, schools offered courses that looked at broader social, cultural, and political conditions associated with periods of war. This New History or New Military History kept “war in the classroom” but often with much less attention paid to war itself (e.g., military campaigns, strategy, logistics, personnel, tactics, etc.).

In parallel with these changes, the field also became increasingly specialized. This was part of a broader societal trend towards “hyper-specialization”. As a consequence, as Brands and Gavin put it, “[a]cademic historians began writing largely for themselves.” The impacts of specialization were not all detrimental to military history; it’s arguably the case that specialized military history courses increased in some places even as war lost some of its prominence in the general survey courses taken by earlier generations.

“to be a successful soldier, you must know history.” - George S. Patton

Over the same time period the Army underwent a similar set of changes. First and perhaps most consequential was the end of the draft and the shift to the all-volunteer force in 1973. This fundamentally changed the Army’s relationship with American society, making it more remote on the one hand and more market-oriented (i.e., it had to actively compete for labor) on the other. Critically, however, the Army also became more professional over this time period.

As the Vietnam War ended, the Army faced a crisis in terms of professionalism. In 1970 then Chief of Staff of the Army General Westmoreland received a study which stated, “There is a significant, widely perceived, rarely disavowed difference between the idealized professional climate and the existing professional climate.” In the following decades, a central focus of the Army, both to repair the force and attract the necessary talent, would be on closing this gap and transforming the force into a modern, lethal, and professional organization.

One of the ways the Army achieved this was by turning itself into a model learning organization. It established the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) in 1973 and led a re-assessment of all aspects of Army training, from the basics of soldiering to the most advanced technical operations. Under the leadership of General William DePuy, TRADOC established cutting-edge programs and improved the quality and utilization of everything from doctrine to equipment.4 Reforms were by no means restricted to the classroom, moreover, as model training sites, exemplified by the National Military Training Center, transformed how units prepared for combat.5

Source: Author’s photo.

In the early days of reform, the study of history was not a central focus for the Army, and may have even been de-emphasized. Greater emphasis was placed on operational considerations and on the socio-cultural dimensions of a professional force. The relatively new civil-military field of political science was taking off during this time and exerting influence that might previously have come from historians. The two most influential books on the subject, Samuel Huntington’s The Soldier and the State and Morris Janowitz’s The Professional Soldier, were published in 1957 and 1960 respectively. Janowitz also founded the Inter-University Seminar on Armed Forces and Society in 1960 and in 1974 launched the Armed Forces & Society journal. The insights from such seminars and scholarly work spoke directly to the Army’s immediate needs as it revitalized its capabilities and repositioned itself with the American people.

Over time, however, the study of history within the Army became the subject of greater institutional effort. As early as 1970, the Army’s Chief of Military History, Brigadier General Hal Pattison encouraged the Chief of Staff (Westmoreland) to reinvigorate the study of history. This eventually bore fruit. In 1979 the Army produced a Guide to the Study and Use of Military History West Point similarly saw increased funding, both from the Army and alumni, to improve academics, including history. It expanded opportunities for civilian professors and allowed cadets to choose a greater number of subjects as a major.6 And as previously noted, the Army, through its Center for Military History, produced a regular series of resources, events, and programming that connected civilian academics with military professionals, all on the topic of military history.

As a consequence of these changes, the Army established for itself a prominent role in shaping the study of military history in America. This was a more specialized and academic endeavor relative to how it had engaged the field before, during, and in the years following World War II, but a critical role nonetheless. Moreover, the Army also put renewed focus on its own study of military history, emphasizing the discipline for all levels of the force through both formal and informal means.

Professionalization and the Public

At the risk of overusing the metaphor, we return once more to the ticker tape parade. In the 1990s New York City held nine parades: five for sports teams, two for war veterans (Persian Gulf War and Korean War, both in 1991), one for Nelson Mandela, and one for Astronaut and Senator John Glenn and the crew of the space shuttle Discovery. The dominance of sports teams among the small number of parades mirrors shifts in how Americans engaged with history.

History still drew crowds in the 1990s. If anything, more Americans than ever were consuming history, but it was dominated more and more by entertainment mediums. The computer strategy game Civilization launched in 1991 to be followed by a range of other military-history oriented video games; the History channel launched in 1995; and in 1998 the film Saving Private Ryan swept the nation. This trend was not unique to history and had much to do with the rise of the internet, but it also reflected shifts in the formal study of history.

History was a much more fractured field in the late 1990s than in 1965 when the golden era of ticker tape parades came to a close. There were many more topics debated by historians and the disagreements were more intense than in the past. This prompted vast outputs of important scholarship and supported greater specialization, including among military history. But all too often these conversations played out in academic contexts with little influence on the broader public.

The Army similarly grew more specialized, professional, and remote during this time period. It’s influence on the study of history decreased even as it built out institutional capacity—at West Point and the Center for Military History for example—to engage in scholarly work.7 By the close of the century, the Army was a smaller and leaner organization than in 1965, with much stronger learning capabilities, but a much weaker connection to the American public.

All of these shifts impacted how the Army and America responded to the 21st century, when history and history wars struck with a vengeance. We will pick this up in Part III.

Note: I benefitted enormously from the advice of Dr. Samuel Watson in compiling this piece. All the opinions put forward are mine and all errors mine alone. But I’m grateful for his input and guidance.

Relatedly, the views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Military Academy, the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the US Government.

Additional Resources:

A good overview of the American study of military history, with robust footnotes, can be found here.

I would also recommend Brian Linn’s new book, Real Soldiering (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2024), about actions the Army took after its wars to recover and improve.

Be Part of Army 250

If you’d like to write a newsletter post, share an educational resource about the Army, or lift up an opportunity for people to connect with the Army (e.g., an event, story, etc.), please contact Dan (dan@army250.us).

Mead, W. R. (2022). The Arc of a Covenant: the United States, Israel, and the Fate of the Jewish people. First edition. New York, Alfred A. Knopf.

There has long been a robust debate among historians about the field’s purpose and professionalism and I incorporate the arguments and ideas of many scholars in this piece. Similarly, the parameters of what constitutes military history has always been a subject of debate.

Lepore, J. (2019). This America: The Case For The Nation. First edition. New York, W.W. Norton & Company.

Gole, H. (2008). General William E. Depuy: Preparing the Army for Modern War. Lexington, Kentucky, The University Press of Kentucky.

Kitfield, J. (1995). Prodigal Soldiers. Washington DC. Potomac Books, Inc.

For more on West Point specifically, see Betros, L. (2012). Carved From Granite: West Point Since 1902. College Station, TX, Texas A&M University Press. In Part III of this series, we’ll discuss how many of trends continued into the 21st century.

It’s important to note that military history encompasses a much broader array of topics than American military history. Similarly, although the Army’s institutional history centers focus on American military history, there are many Army historians with expertise in wars in which the United States was not a participant (and where, in many cases, it did not even exist yet as a nation).