The gold standard for history organizations

The Army and how Americans study and apply history. Part I.

Americans love to argue history. We argue not just over historical events—was Eisenhower’s “broad front” strategy in 1944 a mistake, for example—but over which period of history we are re-living today. Is it the 1930s or the 1830s? Are we facing a new Gilded Age or is it the late 19th century American frontier period that best explains our present moment? Where you fall on these questions is a matter of opinion, but what’s not up for debate is that the U.S. Army helped make the arguments possible.

The Army, as much as any other institution, helped professionalize the study of history and expanded its reach and prominence. From identifying and archiving historical documents to researching and writing on history itself, countless soldiers and Army civilians have played a key role in keeping history alive. This continues today, with the Army serving as a vital source of historical research and scholarship, especially with respect to military history.

The Army’s interest in having a robust history profession is clear. War is inherently connected to politics and, as Edward Freeman once noted, “[h]istory is past politics and politics present history.” A more accurate understanding of historical facts and contexts better enables military professionals to draw lessons from the past and apply them to conflicts in the present. What is notable, however, is how the Army’s efforts to bolster the study of history contributed to the professionalization of the field more generally.

Patriots & Amateurs

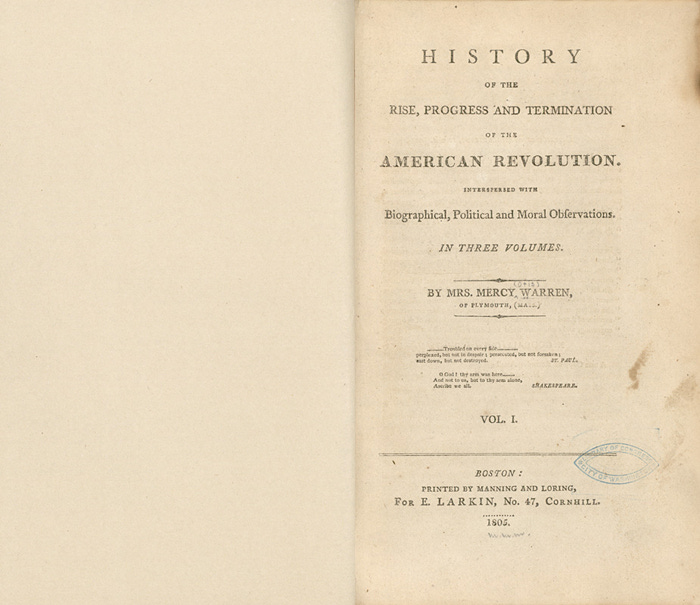

We start with the fact that for most of history, historians were not professionals in the way we understand them today. For example, one of the most prominent histories of the American Revolution was written by Mercy Otis Warren of Massachusetts, a poet, playwright, and political commentator. Her three-volume series, History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution, came out in 1805. Similarly, David Ramsay, who published a history of the Revolutionary War in 1787, was a physician and politician who started writing history, at least in part, because he was imprisoned by the British during the war. The examples of Warren and Ramsay were reflective of the treatment of history across the globe, which as noted by the American Historical Association (AHA), was primarily the domain of “wealthy men with the leisure time to pursue such endeavors did most of the writing of history and collection of historical manuscripts and archives.”

Mercy Otis Warren’s History of the American Revolution. Source: Library of Congress.

Professionalization

The professionalization of history began in earnest in the 18th and 19th centuries. In part this reflected the emergence of research universities in Germany whose educational models inspired similar institutions in America. The Army was an early adopter of this trend: in 1818 Sylvanus Thayer, Superintendent of the United States Military Academy (West Point, established in 1802), provided for a Professor of Geography, Ethics, and History. Although the focus was more on law than history, it began the institution’s foray into professional history.

The Civil War accelerated the Army’s formal engagement with history. In 1864 Congress authorized the War Department to produce a record of the war. This project continued through to 1901. At the same time, the War Department produced a history of the Army’s medical experience. These efforts created a robust foundation of historical documents and analysis, one that continues to serve historians today.

These efforts coincided with initiatives in academia to professionalize the field of history. At the annual meeting of the American Social Science Association in 1884, historians voted to established a separate organization focused on history: the American Historical Association (AHA). The AHA was incorporated into Washington D.C. in 1889 by Congress. The AHA would contribute to the relatively-new Smithsonian Institution, which was dedicated to the “increase and diffusion of knowledge" in America.

The logo of the Center of Military History. Source: Center of Military History.

World War I accelerated all of these efforts. In 1918, the Army established a Historical Branch in the War Plans Division. While the name and scope of this office has changed, the Army has maintained a centralized history office. The war also led to the creation of the American Battlefield Monuments Commission (ABMC), an initiative to construct memorials to the American Expeditionary Force. This effort helped channel resources and personnel, including a young Dwight Eisenhower, towards historical research.

Mobilizing Historians

World War II mobilized the professional historian community in support of America’s war efforts. As noted by the Center of Military History, “[e]mploying mostly civilian professional historians who had practiced their craft, as soldiers, in overseas theaters during the war, the Historical Division embarked on the most ambitious U.S. official history project ever, the United States Army in World War II series.” This merger of civilian and Army historians produced durable bonds that continue to this day and unleashed another wave of professionalization.

Since World War II, the Army has taken a number of steps to deepen its institutional focus on history. In 1969, for example, West Point established a standalone Department of History. The Army created field historian positions and built out doctrine. In 1973, it revised its centralized history office to be known as the Center of Military History (CMH), which has in its vision to be “the gold standard for history organizations.” Finally, in the early 1980s, the Army even established a journal, The Army Historian, to help bolster the engagement with military history across the force. By this point, history as a professional endeavor in the Army had fully arrived, and in doing so, contributed to similar growth and recognition in civilian society.

Cracks Emerge

In the aftermath of World War II it seemed as if a golden age of professional history was emerging. Army historians and members of the force more broadly, regularly engaged in historical research and writing. And during a time of high trust in institutions and professions, the opportunities for historians appeared endless. But cracks were emerging, both within the profession and and the broader American society, including the Army. These cracks would dramatically change how Americans engaged with history; changes and challenges that we continue to feel today.

In Part II of this series, we’ll dive into this story. Stay tuned.

Additional Resources:

CMH has been a great resource for Army 250. Its motto of “Educate”, "Inspire”, and “Preserve” speaks to much of the core purpose behind Army 250. I highly recommend checking out its website and reviewing all the great products it regularly publishes.

A good resource to learn about the combat historians of World War 2 is this 2022 paper in Military Review, History While It’s Hot.

You can learn more about current Army journals and writing at the new Line of Departure website here.

Be Part of Army 250

If you’d like to write a newsletter post, share an educational resource about the Army, or lift up an opportunity for people to connect with the Army (e.g., an event, story, etc.), please contact Dan (dan@army250.us).

Great article, Dan. Especially for those of us who are not as familiar with Army institutions.

It's not really a profitable activity to compare our personal experiences with academic historians because both sets of experiences are valid. But Fouchault and Marx were central to academic discourse between historians where I was taught and when I complain about that in other fora I see a lot of agreement from folks who are currently teaching.