"What do we do with the bodies?"

The Army and how Americans bury our dead

The ground calls on all of us. One of humans’ oldest and greatest fears is to be denied a proper burial. In the Old Testament, for example, when a man from Judah eats and drinks where God commanded him not to, his punishment includes being denied burial with his ancestors: “your body shall not come to your ancestral tomb” (1 Kings 13:22). While attitudes towards burial have shifted over time, with more Americans now indicating a preference for cremation over traditional burials, cemeteries have retained a strong sense of the sacred for many people.

It was not the Army that first sacralized burial rituals and ground in America. As historian Drew Gilpin Faust writes in This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War, “The concept of the Good Death was central to mid-nineteenth century America, as it had long been at the core of Christian practice.”1 But the Army did play an important role in transforming the burial experience in America, in ways that continue to influence us today.

The catalytic event was the Civil War. The magnitude of death unleashed by this war overwhelmed the Army and nation in both an operational and spiritual sense. Logistically, it broke the Army’s ability to efficiently and appropriately process its dead (and those from the Confederate forces). And similarly, by confronting the nation with death on a previously unimaginable scale, the Civil War challenged Americans to wrestle with new meaning for the word sacrifice.

Across both these fronts, the Army eventually helped create new innovations and institutions that altered the practice and purpose of burial in America. Operationally, the Army contributed to the birth of the modern mortuary business, bringing national scale to what had previously been a familial affair. Spiritually, and perhaps more significant for our purposes, the Army pushed the nation to build the first-ever national cemeteries, forever concretizing the concept of national sacrifice. As Faust puts it, “Death created the modern American union—not just by ensuring national survival, but by shaping enduring national structures and commitments.”

Fields of Death

The numbers stagger the mind. In the Civil War, approximately 620,000 soldiers died.2 Taking just the deaths among Union forces, the number is over 360,000, or about 2 percent of the 1860 population. That would be as if 6,500,000 soldiers died today.3

We really have no way to comprehend that magnitude of death. In her 2023 foreword, Dr. Faust talks about America’s experience with the COVID-19 pandemic, which took the lives of approximately 1,100,000 people. Yet as tragic as that figure is, it still pales in terms of overall size and, perhaps even more differentially, density.

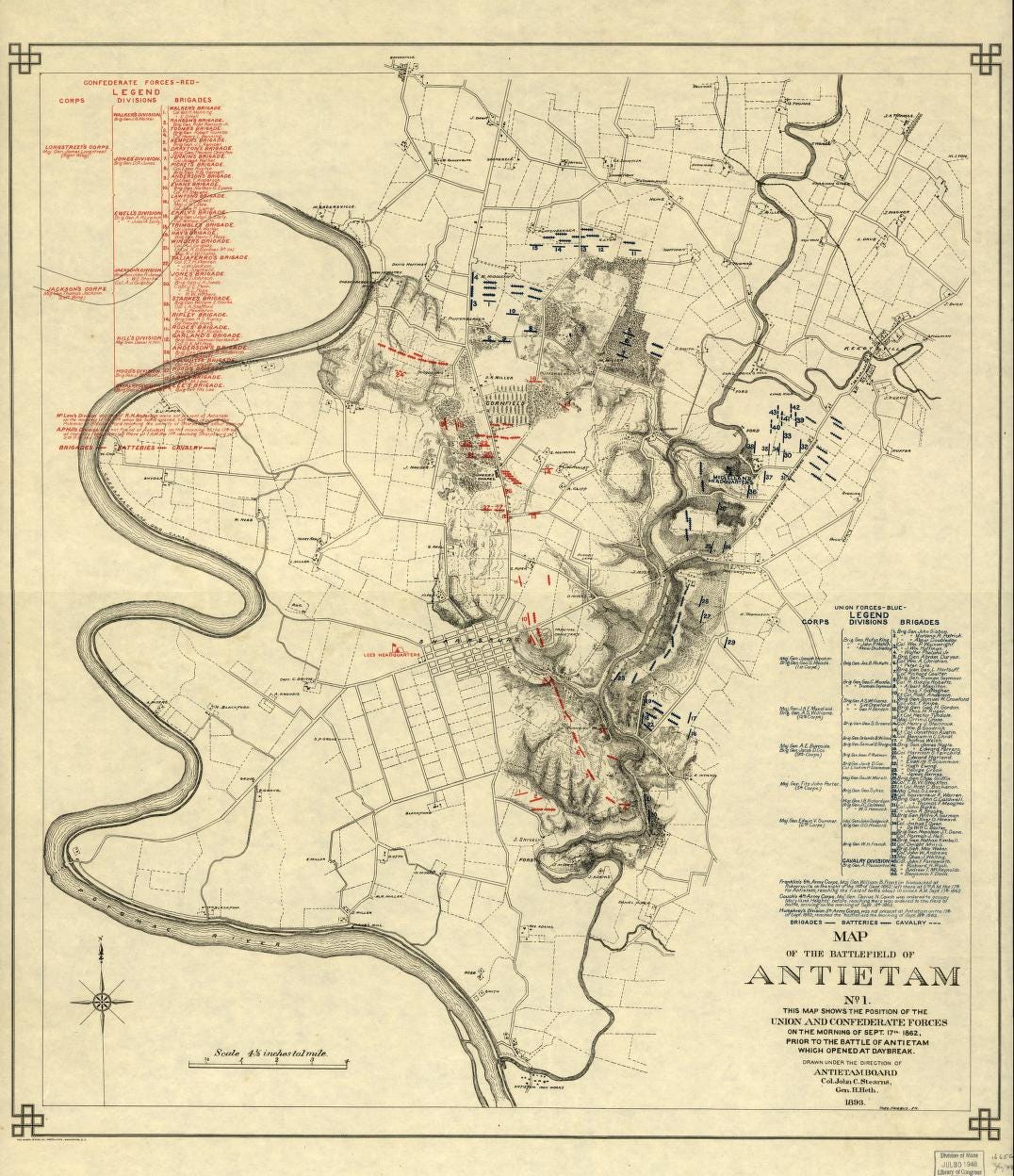

Battle of Antietam. Source: Library of Congress.

The Civil War dead did not fall in a distributed fashion across the entirety of the country; they perished en masse in very specific, often quite small, geographies. At the Battle of Antietam (September 17, 1862), over 12,000 Army soldiers died in one day (about 12 hours to be more precise), on a battlefield of approximately 3,200 acres. 3,200 acres is about four times the size of New York City’s Central Park. Can you imagine 214,000 Americans dying today, in one day, in such a small box of terrain? The answer is no.

Neither could the Army in 1861.

Anticipating a quick, light conflict, the Army failed to mobilize for mass casualties. As late as 1862, Army units took to battle without dedicated ambulance personnel to extract the dead and wounded. But even when the Army had personnel and infrastructure to manage the dead, they were still insufficient to the task. At the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3 , 1863), where over 3,000 Army soldiers died, “so many bodies lay unburied that a surgeon described the atmosphere as almost intolerable.” The smell from the dead would only go away when frost came in October, shortly before President Lincoln arrived to dedicate the Gettysburg cemetery.4

Dedication of the Gettysburg cemetery. Source: Library of Congress.

Being compelled, by desperation or the inadequacy of resources, to leave the dead unburied or half-buried was deeply upsetting for soldiers. As Roland Bowen of the 15th Massachusetts wrote, “This is not how we bury folks at home.”5 In the midst of this desperation, however, both the methods and meaning of death were changing.

“To undertakers, the Civil War also shaped the modern day funeral service.”

Ryan Helfenbein, “The Civil War Creates Change”

From Death An Industry is Born

Thomas Holmes started the Civil War as a captain in the Army and ended it as the “Father of Modern Embalming.” Holmes had already established his proficiency with embalming when the war broke out and his business—he resigned his commission with the medical corps and charged $100 a body—took off as casualties mounted. While best known for embalming President Lincoln, Holmes was one of the key players who helped usher in the funeral and mortuary industry as we know it today.

This industry expanded during the Civil War to manage everything from ferrying the dead off the battlefield to settling bodies in their final resting places. Transportation companies such as the Staunton Transportation, advertised their ability to survey entire battlefields and carefully return bodies preserved “in a natural and perfect condition” to their families. New facilities—what we know as funeral homes—popped up to house the dead before burial, moving this process out of families’ homes and into a commercial setting.

Staunton Transportation Company advertisement. Source: Library Company of Philadelphia.

At the close of the war, in March 1865, the War Department issued “General Orders No. 39, Order concerning Embalmers”, which required licensing and adherence to a specific set of prices. This marked the first steps towards professionalizing the funeral industry. Today there are over 15,700 funeral homes in America.

Our Final Resting Places

In the front yard of the house where I grew up, there is a cemetery. It’s a small plot with just a few graves, all members of the same family that first built the house in the 18th century. This was the norm in early America. Families were responsible for burial for reasons both practical—few commercial mortuary institutions existed—and religious—pious Americans felt strongly the sacred obligations towards the dead. Starting in the mid-1800s, however, this began to change.

In 1831, to address issues of weak infrastructure and overcrowding at church yard burial grounds, members of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society founded Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge. This was the first of a broad, national movement to construct large, communal burial grounds. Over the decades, such cemeteries sprouted up all across the country.

It was the Civil War, however, that imbued grave sites with an entirely new meaning. Up until that conflict, America had no national cemetery for war veterans and their families. In 1862 this changed when Congress passed legislation authorizing the President to “purchase cemetery grounds, and cause them to be securely enclosed, to be used as a national cemetery for the soldiers who shall die in the service of the country.” By 1864 there were 27 national cemeteries in existence.

This legislation created a new national commitment to America’s war dead. This responsibility gained even greater meaning when Congress passed the National Cemetery Act of 1867, directing the War Department to ensure the burial for all soldiers who served in the Civil War. With this act, as Dr. Faust writes, “the federal government legally signaled its acceptance of responsibility for those who had died in its service.”

This responsibility, revolutionary at the time, has remained a cornerstone of America’s relationship with its Army (and military). It is a promise to those in uniform, that should anyone fall in the execution of their duties, Americans will hold them close as our dead and that we, as a nation, will expend every effort to see them laid to rest with respect and honor. The sanctity of that promise, however imperfectly we have honored it at times, is made manifest when we visit Arlington or other national cemeteries.

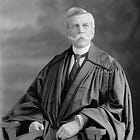

“But in the midst of doubt, in the collapse of creeds, there is one thing I do not doubt, that no man who lives in the same world with most of us can doubt, and that is that the faith is true and adorable which leads a soldier to throw away his life in obedience to a blindly accepted duty, in a cause which he little understands, in a plan of campaign of which he has little notion, under tactics of which he does not see the use.”

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr, “A Soldier’s Faith”

The Full Measure of Faith

The faith Justice Holmes speaks of was justified again and again in the Civil War. The willingness of soldiers to suffer unbelievable numbers of casualties, only to march once more into battle, stunned and inspired the nation. From the depths of these sacrifices emerged a revolutionary commitment from America to find, bury, and honor its war dead. This commitment, while focused initially on the hundreds of thousands of Civil War dead, has had no sunset clause. The physical embodiment of this commitment, our national cemetery system, remains today a home and memorial for all those who give what Lincoln described as the “last full measure of devotion” to our country.

Army 250 is a passion project celebrating the Army’s 250th birthday in 2025. If you enjoyed this piece, please share it with your networks. If you are a new reader, please subscribe below.

Additional Resources:

PBS produced a series, Death and the Civil War, based on Dr. Faust’s book.

Two of the trade associations for funeral directors and morticians produce interesting survey data on Americans’ feelings about and plans for death. You can see examples here and here.

Though not directly tied to the Civil War, America’s Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency reflects a similar commitment to our nation’s service members and their families as to the one that led to the national cemetery system. Since the Department of Defense established a Special POW/MIA Office in 1964, this agency (in various organizational forms) has returned approximately 1,500 personnel.

In February 2025, Army 250 wrote about Oliver Wendell Holmes and his speech, “The Soldier’s Faith”.

Faust, Drew Gilpin. (2008). This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. New York, Penguin Random House.

In her 2023 foreword to This Republic of Suffering, Dr. Faust notes that some scholars now place the total dead at over 700,000.

Throughout I refer only to the Army when talking about Civil War fatalities, but embedded in the top line figures are deaths of sailors and Marines. The Army suffered the overwhelming proportion of deaths, but we should not discount the sacrifices made by those in the sister services nor the overall contributions the Navy and Marine Corps made to the fight.

Faust., 69.

Ibid., 61.

Great post. I walked through the Leavenworth cemetery yesterday which has graves for 762 unknown Union soldiers.

That guy certainly understood the OODA “loop” sketch over 100 years earlier! Emergent opportunities to capitalize on exist for those whose the field differently!