First Shot and First At-Bat

The Army and America's National Pastime

“Democracy is the score at the beginning of the ninth.”

E.B White “On Democracy”

Baseball is spliced deep into America’s DNA. In the midst of World War II, author E.B. White included baseball in his stirring articulation of democracy, trusting that the metaphor would be universally understood by his American audience. It’s been fifty years since football displaced it as America’s favorite sport to watch, yet baseball still looms as our national pastime. The romance of the sport taps deep into the most compelling parts of nostalgia and hope: baseball is when Ray gets to play ball with his dad as hundreds of cars come to watch in Field of Dreams. But it’s also the ultimate underdog story, with mavericks like Billy Beane in Moneyball pulling together teams of outcasts that topple giants. Even at its most unromantic, with teams whose budgets rival the GDPs of nations, baseball still pulls us in with its spectacle and grace, epic rivalries, and the hope we hold onto that one day we might step up to the bat. I’m far from the world’s biggest baseball fan, but when the opportunity arose to practice a few swings at Fenway, it did not matter that the stadium was empty and the balls thrown by a machine, it was magic.

But before all that. Before the magic and the spectacle. Before YES Network and Moneyball. Even before Murderers’ Row. Baseball was Army.

Or was it?

Some call it a myth. Others say the evidence is “pathetic”. But whatever shortcomings there might be in the historical record, Army veteran Abner Doubleday is officially credited as inventing baseball in 1839, when he was a cadet at the United States Military Academy (West Point). This means every home run, strikeout, and double-play is part of the Army’s story.

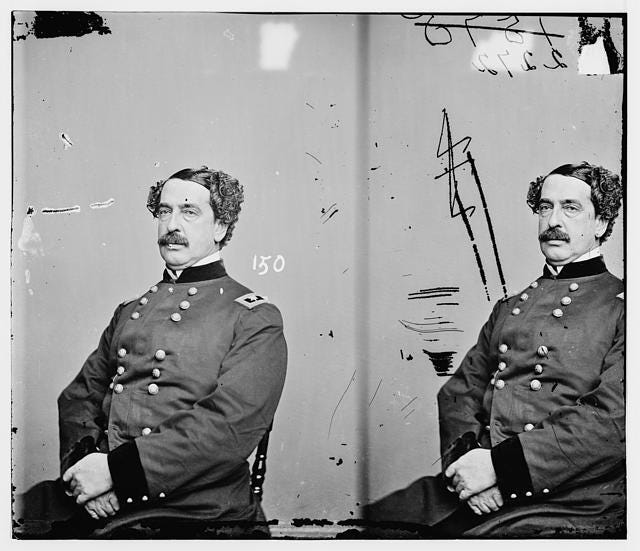

Abner Doubleday. Source: Library of Congress.

The tale behind Doubleday’s fame is one for the ages. Baseball began in earnest following the Civil War, but in 1907, a group of baseball executives, led Albert Goodwill Spalding—a former pitcher who went on to found the sports equipment giant Spalding—formed the Mills Commission, to identify the origins of the game. The commission head was A.G. Mills, the president of the National League and friend of Abner Doubleday.1 In April 1908, the Commission produced its final report declaring, “The first scheme for playing baseball, according to the best evidence obtainable to date, was devised by Abner Doubleday at Cooperstown, NY, in 1839." The evidence for this determination was testimony from a man named Abner Graves, who wrote a letter saying he saw Doubleday invent the game. The Commission apparently did not investigate the claim and Doubleday, having been deceased for over 15 years, was unable to confirm or deny the attribution. Whatever its veracity, the announcement provided baseball with a powerful origin story.

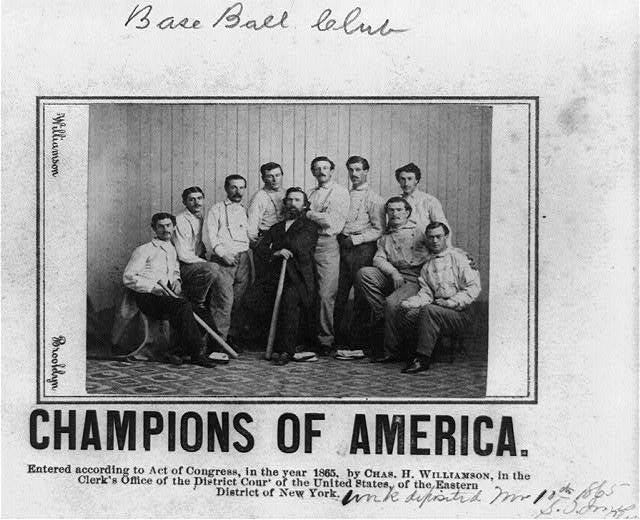

Early baseball—the Atlantics of Brooklyn Baseball team, 1865. Source: Library of Congress.

General Doubleday, while never as famous as Grant, Custer, or Sherman, was nonetheless well-known for his military exploits and leadership. He supposedly fired the first shot in defense of Fort Sumter, South Carolina in 1861; he fought bravely at Antietam and Fredericksburg, among many battles; and at the Battle of Gettysburg, he assumed command of I Corps when Major General John Reynolds was killed and led 9,500 Army soldiers in holding off more than 16,000 Confederate soldiers. Christopher Gwinn, Chief of Interpretation and Education at Gettysburg National Memorial Park, calls this Doubleday’s “best day during the Civil War.” Following the war, Doubleday commanded an all African-American unit in Texas, where he set up baseball games to build morale for his unit. He was, by all accounts, an impressive leader of character and a patriotic American; in other words, a worthy founder for America’s national pastime.

The Mills Commission’s decision has had major impacts. The Baseball Hall of Fame is located in Cooperstown, New York largely due to its connection to the Doubleday origin story; the baseball field at West Point is Doubleday Field (as is the field in Cooperstown); and America held a celebration of baseball’s centennial anniversary in 1939—100 years after Doubleday supposedly created the game. Doubleday—and through him the Army—are thus now deeply woven into the fabric of the game.

But Doubleday is far from the only connection between baseball and the Army. Legends such as Ty Cobb, Joe DiMaggio, Jackie Robinson, and Willie Mays, among many others, all served in the Army. More recently, West Point graduates Chris Rowley and Jacob Hurtubise played in the MLB. One need only watch a game at Doubleday Field to see the bond between the Army and baseball remains strong.

My baseball career ended early; it started going downhill when they removed the batting tee. But my attachment to the sport runs deep. About twenty years ago, when my father-in-law, a lifelong, dedicated baseball fan, was battling cancer, I asked the West Point baseball team to sign a poster for him. They rallied essentially the whole team to sign a beautiful wall print. This meant a great deal to me, to my then-fiancée (now wife), and to my father-in-law. He passed away not long after and I’ll be forever grateful for the gift baseball gave us during a hard time. And now as a father, I look forward to bringing my son to many a game as he gets older. I can’t teach him much about how to swing or pitch, but I can tell him about the magic of baseball and its long roots in America, which might just include a young West Point cadet organizing a game out in Cooperstown almost two hundred years ago.

Army 250 is a passion project celebrating the Army’s 250th birthday in 2025. If you enjoyed this piece, please share it with your networks. If you are a new reader, please subscribe below.

Additional Resources:

The National Baseball Hall of Fame’s website is here.

West Point Baseball’s website is here.

You can learn about MLB's military appreciation programs here.

Abner Doubleday is buried at Arlington; you can learn more about his gravesite here.

Abraham Gilbert, or “A.G.” Mills, was also an Army veteran. He served first as an enlisted soldier and then as an officer with Army in the Civil War. When doing research for this article, I only found one reference to AG Mills and Doubleday being friends and no indication that this friendship played a role in the Commission’s decision.

Your quote about your career going downhill after the tee was removed cracked me up. Great piece as always