America and the Korean War

Americans have never truly known this war nor truly met its veterans

On November 23, 1984, America fought a 30-minute battle with North Korea. It started when Vasilii Yakovlevich Matuzok, a Soviet translator, bolted across the Military Demarcation Line (MDL) separating North and South Korea. Approximately 20 North Korean soldiers pursued Matuzok and began firing on him. In response, American and South Korean soldiers converged on the scene and engaged the North Koreans. Within minutes, the U.S. and South Korean forces overwhelmed the North Koreans, but before they could apprehend the intruders, a cease fire was called. The North Koreans took their dead, wounded, and uninjured back across the MDL. Three North Korean soldiers were killed and five wounded; one American soldier, Private Michael Burgoyne, was injured; and one South Korean soldier, Private First Class Jang Myong-ki was killed. Matuzok survived the fight and remained free.1

This battle occurred two months after I was born. It joined a long list of violent events along the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) that started almost immediately after military commanders representing the United Nations, North Korea, and China signed an armistice in 1953. Today, in 2025, this list continues to grow longer.2 Prior to doing research for Army 250, I knew about a handful of these incidents, such as the 1976 attack where North Koreans killed two American soldiers with clubs and axes, but most of them were new to me.3 In many ways, this sums up America’s relationship with the Korean War: ever present and always overlooked.

A War We Never Knew

The Korean War Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C. bears the following inscription: "Our nation honors her sons and daughters who answered the call to defend a country they never knew and a people they never met." It’s a beautiful, poetic statement, one worthy of the sacrifices so many made on the Korean peninsula. But it is also tragically ironic in that the Korean War is a war Americans never knew and its veterans a people they never met.

In this sense, the words inscribed on the memorial remain incomplete. They are a promise carved in stone, but not yet enshrined, as is said with the Lincoln Memorial, “in the hearts of the people”. This year marks the 75th anniversary of the start of the war, an appropriate milestone to consider the opportunity and responsibility we have to fulfill this promise our nation made.

Korean War Veterans Memorial. Source: Department of Defense.

The Full Weight of the War

We forget the Korean War not because it was in any way insignificant. Even just considering the years 1950 to 1953, Americans fought in Korea for about as long as we fought in World War II.4 Close to two million Americans served in the Korean theater of operations. Aout 37,000 Americans were killed, over 92,000 wounded, and approximately 8,000 declared missing in action.5 Over 150 service members received the Medal of Honor for actions during the war. It was a long, brutal, war, fought in hellish conditions, and it directly affected millions of Americans.

It was also a major, geopolitical event. It turned the Cold War hot and brought home the terrific magnitude of violence we could experience in our conflict with the Communist bloc. As T.R. Fehrenbach wrote in 1963, “that such a skirmish between the earth’s two power blocs cost more than two million human lives showed clearly the extent of the chasm beside which men walked.”6

It caused America to fight a massive and sustained conflict with communist China and permanently altered our relationship with the Asia-Pacific. The Korean War set the context for both America’s Vietnam War and South Korea’s rapid economic growth as one of the four Asian Tigers.78 And the war’s influence continues to be felt—the US-South Korea Mutual Defense Treaty, signed in the aftermath of war, remains, in the words of the U.S. State Department, a “linchpin for security and stability in the Indo-Pacific”, with approximately 28,500 American service members still stationed in South Korea today.

The war’s impacts were not just limited only to foreign affairs; it was a transformational event for both the military and American society. On the military side, the Korean War featured one of the highest-profile ruptures in the history of American civil-military relations, when in 1951 President Truman fired General Douglas MacArthur, the commander-in-chief of the UN forces in Korea and one of the most famous military leaders in America.9 It also was the “first large-scale, jet-on-jet combat in history” and the first conflict to put an newly-independent Air Force to the test. Military strategist John Boyd, astronauts John Glenn, Buzz Aldrin, and Neil Armstrong, and baseball Hall of Famer Ted Williams all flew in the Korean War.

Cartoon of President Truman wearing General MacArthur’s hat; sketched in 1950 when many Americans viewed Truman as less capable as a commander-in-chief. Source: Library of Congress.

The Korean War also saw the first deployment of the newly-created Army Special Forces. Though variations of Special Forces (as we understand it today) had existed prior to this point, the first Special Forces unit, the 10th Special Forces Group, was activated in June 1952. 99 Special Forces soldiers deployed to the Korean War as individual replacements in 1953. The headquarters for these units has continued to serve as the home for Special Forces and is now known as the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School.

Finally, with respect to its influence on American society, the Korean War was a transformational experience on matters of race and gender. It was the first large-scale conflict where the American military was racially integrated and women had permanent military roles. In 1948, President Truman issued Executive Order (EO) 9981, desegregating the military, and signed the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act, a bill authorizing women to serve in permanent (i.e., both in peace and war) roles in the regular military. Over 600,000 Black Americans and approximately 120,000 women served in the Armed Forces during the Korean War period. One of the roles women served in during the war was as nurses as Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals (MASH), the main location for the hit television show M*A*S*H.10

Draft text of the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act. Source: National Archives.

For all these reasons and more, historian Clay Blair rightly described the Korean War as one of the most consequential conflicts of the twentieth century.11 But even this understates its importance, as a more accurate characterization is that the Korean War is one of the most consequential conflicts in the world. There has been no peace treaty. South Korea remains technically in a state of war with North Korea and America has a deep, active, and formal defense alliance with South Korea. A reassessment of the war’s place in our public consciousness, to give the war the significance and depth it truly merits, is long overdue.

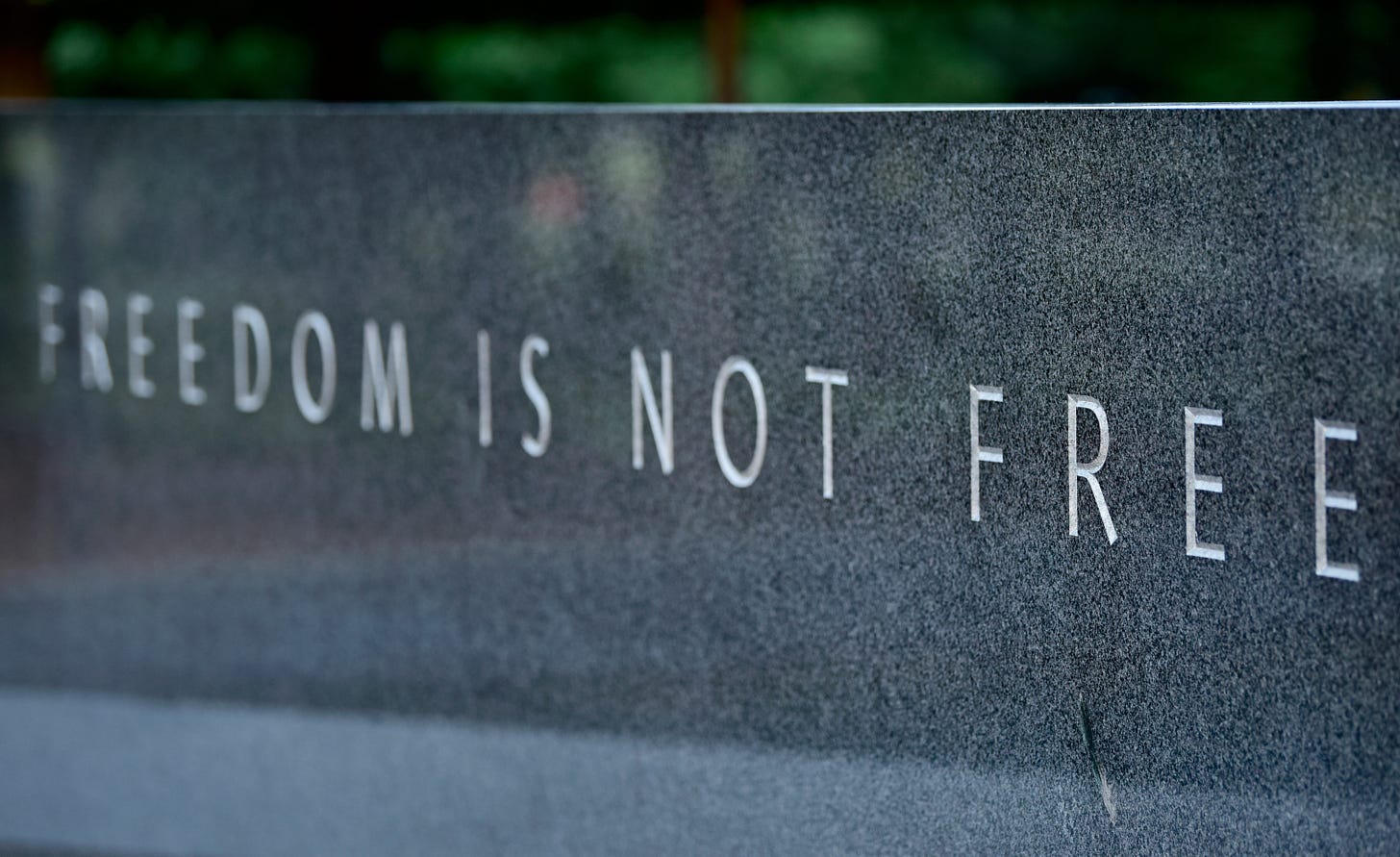

Freedom is not Free

What might such a reassessment look like? To begin with, we can read books on the war, its veterans and all those directly impacted by the conflict. The list of books on the war should be longer, but there is still no shortage of great reads, such as: Clay Blair’s The Forgotten War, David Halberstam’s The Coldest Winter, On Hallowed Ground by Bill McWilliams, This Kind of War by T. R. Fehrenbach, Valleys of Death: A Memoir of the Korean War by Bill Richardson and Kevin Maurer, and Hampton Sides’s On Desperate Ground, among others.

We can also go out and meet Korean War veterans. There are still hundreds of thousands of veterans still alive today. There are also many Korean War veterans’ stories available via the Library of Congress’s Veterans History Project.

Finally, we can visit memorials. In 2022, the national Korean War Veterans Memorial added a new Wall of Remembrance, which shows the names of 36,574 American servicemen and 7,114 Koreans (who were part of the Korean Augmentation to the US Army or KATUSA forces) who gave their lives during the war. These names are given additional presence through the 19 statues situated on the “Field of Service”; these statues, when combined with their reflections, create a total of 38 images of soldiers, inviting us to see the 38th parallel (the demarcation between North and South Korea) in our minds. The statues also put faces to the war, a critical feature given its overall obscurity. During the development process for the memorial, General (ret.) Richard G. Stillwell, chairman of the Korean War Veterans Memorial Advisory Board, said to the designers, “Just show their faces. Show their faces.”

The 19 statues of the Korean War Veterans Memorial. Source: National Park Service.

It is the memorial’s job to show us their faces, but it is our job to see their faces. It is our job to see their war. In doing so, we can turn it into our war in our minds, memories, and hearts. And in doing so, we can each carry forward the war’s most powerful message, written in 10-inch silver letters at the memorial: “Freedom is not free.”

Source: DVIDS.

Army 250 is a passion project celebrating the Army’s place in American society. If you enjoyed this piece, please share it with your networks. If you are a new reader, please subscribe below.

Additional Resources:

You can learn about the Korean War Veterans Memorial Foundation on its website here.

One of the Americans involved in the battle was Richard Lamb, who would go on to be a special operations legend. Lamb was awarded a Silver Star for his actions on the DMZ

One of the main characters in Rick Atkinson’s book, The Long Gray Line, about the West Point class of 1966, is Art Bonifas. Captain Art Bonifas was one of the two Americans killed in the 1976 attack by North Korea. He only had three days left in his tour and when he died, he left behind a young wife and three young children. Camp Bonifas along the DMZ is named after him and he is buried at West Point.

Blair, Clay. The Forgotten War: America in Korea 1950-1953. New York: Random House, 1988.

As of 2024, there were still over 7,000 Americans unaccounted for from the Korean War.

Fehrenbach, T.R. This Kind of War: The Classic Korean War History. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, Inc. 2008.

As Fredrik Logevall documents in his history of America's involvement in Vietnam, the Korean War significantly accelerated and expanded U.S. military activity in Indochina. When North Korea invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950, the Truman administration had already decided to provide aid to the French in their fight against the Viet Minh, but the war prompted Truman to increase support for the French. As U.S. forces moved into combat on the Korean peninsula, planes arrived in Saigon with American resources for the French. This connection continued under the Eisenhower administration. In December 1952, for example, incoming Secretary of State John Foster Dulles told French leaders that Eisenhower viewed Korea and Vietnam as a single front. (Logevall, Fredrik. Embers of War: The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America’s Vietnam. New York: Random House, 2013.)

South Korea is now the 12th largest economy in the world, with a GDP of around $2 - $3.4 trillion (depending on how you calculate it). In contrast, North Korea’s economy is likely closer to $20 to $30 billion, though it is more difficult to calculate an accurate figure.

Truman’s firing of MacArthur is one of the most heavily studied events in U.S. civil-military relations. At first, the firing was poorly received by the American public. MacArthur received a hero’s welcome, with millions attending a parade in his honor and Congress inviting him to give a speech before a joint session. Subsequent congressional hearings, where most of the active military leadership criticized MacArthur’s leadership, moved things in a more favorably direction for Truman.

M*A*S*H was set in Korea, but understood as commentary on the Vietnam War.

Blair, The Forgotten War.