Why this Army?

The Next Phase of Army 250

Henry Knox, in his 1790 “Report on the Militia”, wrote:

“The idea is therefore submitted, whether an efficient military branch of government can be invented, with safety to the great principles of liberty, unless the same shall be formed of the people themselves, and supported by their habits and manners.”

The idea. The American Army, our military more generally, and most importantly, the relationship between the military and the society it serves started as just that, an idea. Could a standing Army exist without irrevocably infringing on citizens’ freedom? Could a nation dedicated to the principles of liberty and equality also produce soldiers willing to serve and fight in an institution that must necessarily demand sacrifices of liberty, to include potentially the loss of one’s life? These questions had little to no historical precedents back in the early days when Henry Knox was thinking about how a new nation could best manage its defenses.

These questions remain vital for us today. Nothing in the relationship between the military and American society is a given; it will only be what we make of it. I am optimistic and confident we can steward this responsibility honorably and decently. But it will not unfold of its own accord.

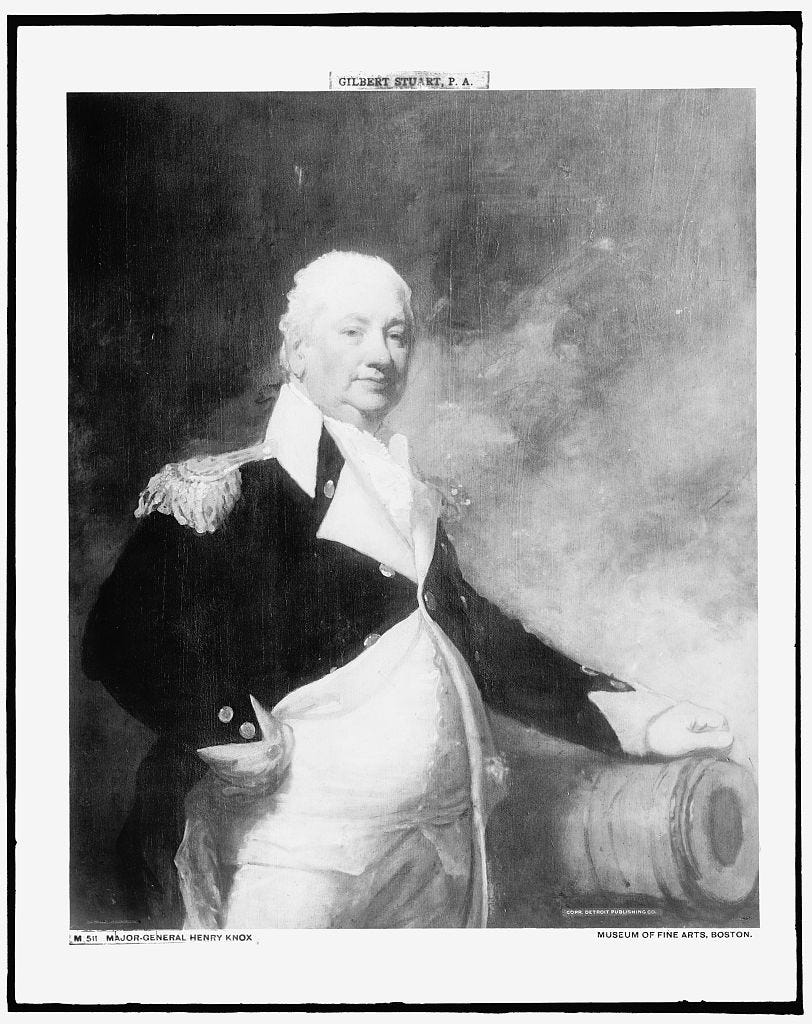

Henry Knox. Source: Library of Congress.

So in this next phase of Army 250 I will be broadening my focus. For the past year and a half my goal has been to lift up the many ways the Army has influenced American society and culture, with an emphasis on its significance outside of battlefields and wars. My hope was to make visible the many ways the Army is America and to illuminate connections which have become hidden in our era of an all-volunteer force. Going forward, I will shift to consider the question of why. Why this Army? Why this military?

My focus will be on pivotal moments throughout history that shaped the relationship between America and her military. Some of these events are well-known, such as President Truman’s clash with General Douglas MacArthur during the Korean War; many others less so.

The military is a vital civic institution, yet we dedicate relatively little energy in civics or history class to understanding it in the same way we might look at the Congress, the Executive Branch, or Supreme Court. We rarely ask ourselves why is it that we no longer have a Secretary or War and instead have a Secretary of Defense? Or why is the National Guard both a Federal and State institution? Why is it we have defense contractors? Why is it that service-members must concede some rights and liberties, but preserve others? These questions get to the heart of how our republic has created the most powerful military in the world, yet one that has never mounted a serious effort to overthrow the civilian leaders; an accomplishment basically unprecedented in history.

Some of our questions will have straight-forward answers; most will not. I start this new phase as a fellow journeyman with you. I will be learning alongside of you. I have no agenda other than encourage all of us to dedicate as much civic learning towards the military as we do the other institutions of government.

Mechanically, I will be writing less frequently. My goal will be to publish a newsletter once a month. I also expect to write in a more chronological fashion, though I acknowledge moving from the past to the present can sometimes create a false sense of order and pre-determinism. I’ll do my best to guard against this.

I’ve benefitted enormously from your support and partnership throughout the first phase of Army 250’s existence. I look forward to us continuing together in the months ahead.

Army 250 is a passion project exploring and celebrating the unique relationship between Americans and their military. If you enjoyed this piece, please share it with your networks. If you are a new reader, please subscribe below.

Additional Resources:

Henry Knox is one of the less well-known yet pivotal figures in American military history. He served as a senior general and head of artillery in the Continental Army, and then as the first Secretary of War. One of the more recent biographies is Mark Puls’s, which came out in 2010—https://www.amazon.com/Henry-Knox-Visionary-American-Revolution/dp/0230623883.