The Army Professionalizes America or Vice-Versa?

How the Army helped usher in the rise of professionalism in the 20th century

Last week, for Constitution Day (September 17, the day the Constitution was signed in 1787), the Army University Press released a new video, “The Soldier and The Constitution.” The 14 minute video talks about the relationship between the military and the government in the U.S. and the relationship between the military and the broader society, stressing the Constitutional foundations of a professional, nonpartisan force. The video and this theme are valuable in and of themselves, but they also speak to a concept that has broad implications beyond the military: professionalism. The Army’s intense drive to instill a healthy culture and ethic of operating under civilian control, as required by the Constitution, contributed a great deal to the rise of professionalism in the 20th century.

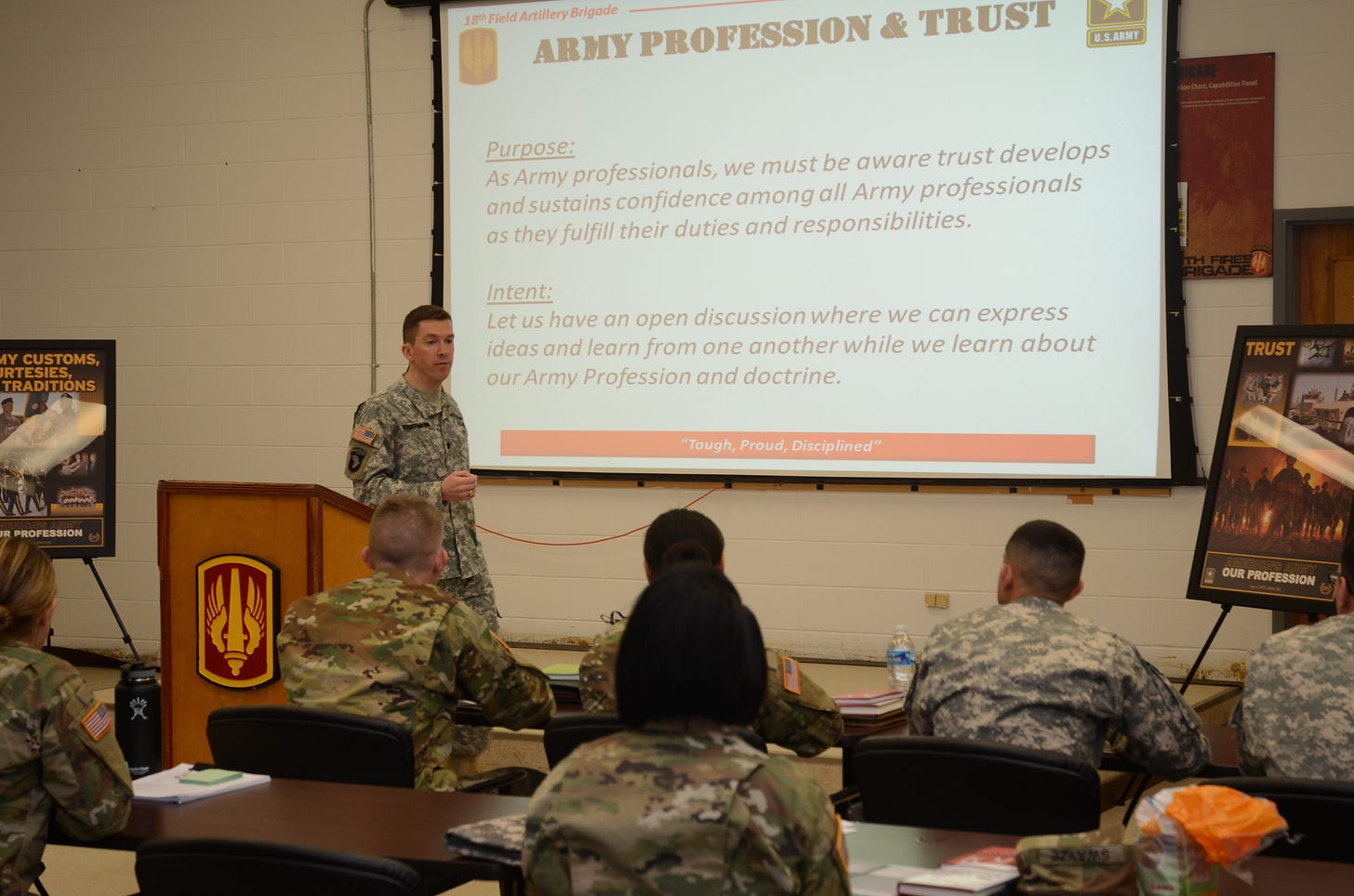

Source: DVIDS.

The advent of World War II and the mass mobilization of American society generated new interest in understanding and shaping what is now called civil-military relations. Books such as Samuel Huntington’s The Soldier and the State and Morris Janowitz’s The Professional Soldier, two of the most influential tracts on civil-military relations, both came out in the late 1950s, early 1960s; and, while they are considered to have divergent prescriptions for the military and political actors, they both center on the idea of a professional military.

Huntington argued professions have expertise, a defined group identity and structure or “corporateness”, and a responsibility to the broader society. Huntington did not invent this definition of professionalism as sociologists had for decades been articulating a set of attributes that delineate professions from vocations, but Huntington’s work, along with that of Janowitz and others focused on the military, took on greater meaning as World War II veterans entered college at unprecedented rates and then joined what was increasingly a professional workforce. We might think of this as the Army professionalizes America 1.0, where a generation whose formative experience was serving in the military, most commonly the Army, went on to assume positions as managers as many fields professionalized in the 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s.

The Army professionalizes America 2.0 came after Vietnam. Here, the influence came due to the Army’s successful, decades-long effort to professionalize the force following the end of the draft in 1973. In this process, as chronicled in books such as Prodigal Soldiers: How the Generation of Officers Born of Vietnam Revolutionized the American Style of War, the Army implemented—and at times, was compelled to implement by its civilian leadership—a dramatic overhaul of personnel policies, training, and strategy, all with an emphasis on instilling professionalism. In large part due to these efforts, public confidence in the military started to increase dramatically.

In the late, 1970s, only 50 percent of Americans expressed confidence in the military. By the last 1980s, it was closer to 70 percent and this trend has (mostly) continued well into the 21st century. In 2016, when analyzing a large-scale public opinion survey of Americans’ views towards the military, scholar Kori Schake and retired USMC General Jim Mattis noted that a significant driver of sustained public confidence in the military through the war on terror was that Americans felt the military was professional—that it had high integrity, expertise, a dedication to the society, and a willingness to improve itself.

As alluded to in the title to this post, however, it is not just that the Army has professionalized America, the opposite is true as well. During both the post-World War II period and the post-Vietnam reform era, political leaders, civilian-military relations scholars, and many other civilians played significant roles in driving change in the Army. As Kori Schake and others have noted, one of the reasons why the military has remained such a professional institution is that politicians, policy-experts, academics, and other advocates—as well as many individuals within the force—continuously agitate over efforts to bolster civilian-military relations.

In this sense, the are enormous benefits the more the Army engages with American society. As an institution, it has much to teach and share about cultivating a professional workforce and culture. But it also needs to continuously learn from and respond to input from the American people, both about specific practices and ideas of professionalism and about how to best serve and represent the American people. The Army’s 250th birthday next year is an opportune moment to cultivate such engagement.

Additional Resources:

Check out an article by Colonel Todd Schmidt, PhD, the Director of the Army University Press, on the topic of the Soldier and the Constitution.

Be Part of Army 250

If you’d like to write a newsletter post, share an educational resource about the Army, or lift up an opportunity for people to connect with the Army (e.g., an event, story, etc.), please contact Dan (dan@army250.us).