The Army & the "Little Platoons" of American Life

How the Army has shaped American associational life

If scientists could ever break down the secret sauce to America’s exceptional story, they’d likely discover one of the main ingredients is our robust associational life. As Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in Democracy in America,“Wherever, at the head of a new undertaking, you see in France the government, and in England, a great lord, count on seeing in the United States, an association.” Americans’ propensity to organize and join together to solve problems, make progress, and otherwise enrich our social and civic lives has long been a critical engine moving the country forward.

Source: DVIDS.

In part this is structural. The U.S. Constitution imposes multiple layers of checks and balances on government while protecting, through the First Amendment, an explicit right to assembly. But Americans’ associational life is also a distinct cultural phenomenon. Writing a century after de Tocqueville, historian Arthur Schlesinger called America a “Nation of Joiners.” While the Army is not the only institution that has played an outsized role in shaping this culture, its imprint has been undeniable.

Beginning with the Revolutionary War, the Army has served as one of the main conduits through which people gained the skills, experiences, and relationships necessary to organize effective associations. Army officers formed the Society of the Cincinnati, for example, in May of 1783 in order to sustain the history of the nation’s founding, advocate for the welfare of soldiers and veterans, and maintain the bonds of friendship and support across the officer corps. '

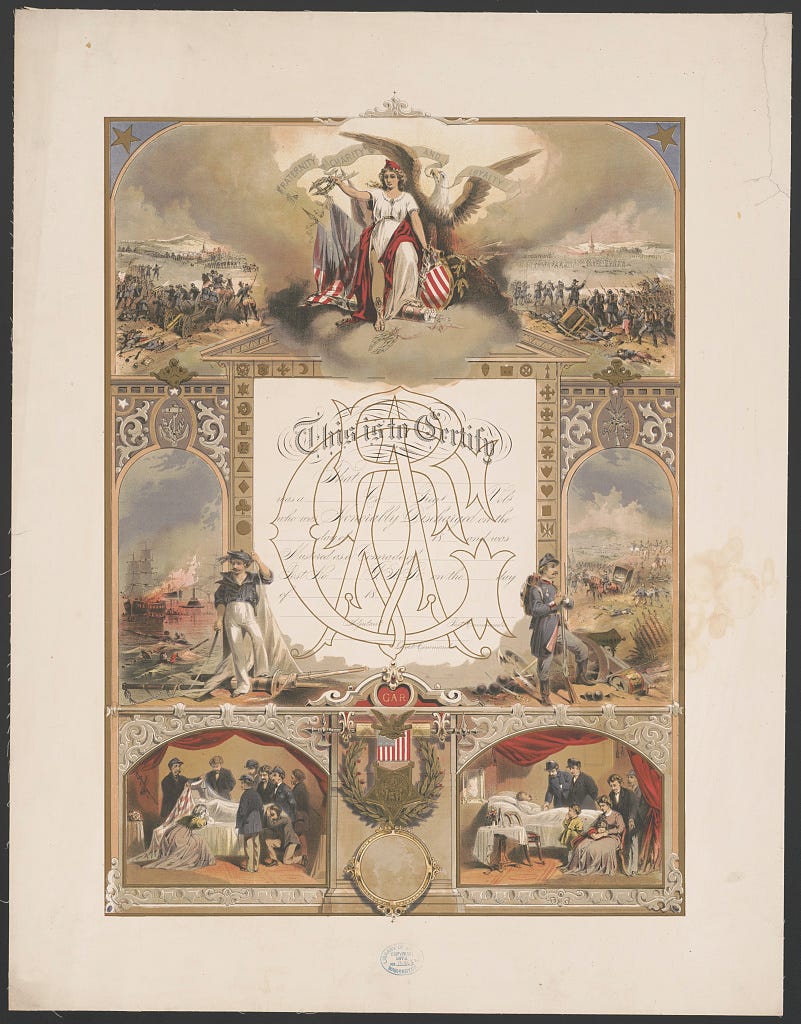

With every subsequent major military conflict, Army veterans went on to create some of the largest and most influential associations in American life. The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), an association of Army veterans from the Civil War, listed over 400,000 members on its rolls in 1890. This included a number of Black Civil War veterans, with the GAR being integrated at the national level, though some posts at the local level remained segregated by race.

Veterans of the Spanish-American War and the Philippine Insurrection founded the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) in 1899; World War I veterans founded the American Legion in 1919. By the late 20th century, those organizations counted over 2 million and 3 million members respectively. Veterans from World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War all went on to found and lead large veterans organizations.

Yet, the Army’s influence on American associational life extends far beyond organizations founded primarily to serve and support the veteran and military family community. Veterans have long served as founders or active members for much of the most active and effective associations across American history, from the Masons to the YMCA, Urban League, and Red Cross, among thousands and thousands of organizations. Scholar Theda Skocpol, in Diminished Democracy: From Membership to Management in American Civic Life, a history and diagnosis of American associational life, identified military veterans as among the most active associational members.

There is a logical connection between the Army and American associations. In order to be effective, associations require leaders and members who can organize people with different views and backgrounds, orient the organization towards a common mission, and then execute on a range of operations, including running meetings, collecting dues, publishing information, and advocating for policy changes. The Army has long cultivated such abilities within its ranks. It’s not for nothing that conservative British philosopher and politician, Edmund Burke, described the community-level organizations and settings within with people exist as “little platoons.”

Today, this story continues. Veterans in America today are more likely than their non-veteran peers to vote and volunteer. Veterans from the Global War on Terror era have founded a range of high-impact associations, such Team Red, White, and Blue, which describes itself as the leading health and wellness community for veterans; The Mission Continues and Team Rubicon, organizations which empower veterans to lead service and disaster-response operations; +More Perfect Union, which is building “brickyards” across the country where service-oriented leaders focus on reducing polarization and bringing communities together; and, Vet the Vote, an initiative to encourage veterans and military families to serve as poll workers. (Disclaimer: I consult for and help lead Vet the Vote.)

From my own personal experience, I have seen more and more Army veterans active in associational life, especially with respect to groups that work to address polarization in the country. I write this at a time when many Americans feel socially disconnected and where associational life feels fractured and often politicized. And while I don’t have a crystal ball, I feel one thing is clear: when historians look back at this period and chronicle the groups that helped reinvigorate a sense of unity among Americans, they will find ample connections to the Army.

Additional Resources:

Library of Congress Exhibition, Join In: Voluntary Associations in America.

U.S. Senate Joint Economic Committee 2017 report: What We Do Together: The State of Associational Life in America.

The U.S. Surgeon General’s 2023 report—Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community.

Be Part of Army 250

If you’d like to write a newsletter post, share an educational resource about the Army, or lift up an opportunity for people to connect with the Army (e.g., an event, story, etc.), please contact Dan (dan@army250.us).