From Strength to Strength

The Army and American Foreign Policy: A Case Study of Singapore

Tens of millions of Americans travel abroad each year, but for much of the world, contact with the U.S. Army is the first and most meaningful connection to our country. This has been the case since the nation’s founding, but the Army’s diplomatic role grew exponentially following World War 2. Today America has hundreds of military bases across the world and hundreds of thousands of military personnel–many of whom are in the Army–serving internationally on any given day.

This week in Army 250 we look at one case study of the Army’s influence in international affairs. As a young lieutenant I was fortunate to spend a year studying at Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in Singapore. NTU is a fantastic university and home to the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), a top strategic studies school. While attending a course at RSIS, I met a scholar and reservist from the Singaporean military, Samuel Chan. Since then, Samuel has been a friend, mentor, and advisor; he’s spent time in Afghanistan, America, and across Asia and the world, learning and teaching about military affairs.

He graciously agreed to be interviewed for Army 250 on his experiences with the U.S. Army and his perspectives on its relationship with Singapore. What follows is a lightly-edited version of our e-mail exchange.

Hi Samuel, thank you for joining Army 250. To help our audience get oriented, can you please share a bit of background–when did you first join the Singaporean Army? What was your branch, which I believe is called formation in Singapore?

I enlisted into the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) on 15 February 1996 after finishing high school in 1995. This was part of my national service (NS) obligations as a Singapore citizen. The NS call up is something that more than a million Singaporean men have experienced since 1967. One is channelled into the SAF for military defence, the Singapore Police Force, or the Singapore Civil Defence Force (SCDF). The SCDF capabilities include emergency medical services, hazardous materials, and the fire brigades.

I received a letter from the Ministry of Defence informing me of where to report, the date, the time, what to bring, and what not to bring. I served 30 months fulltime as a national serviceman in the army and the journey was fairly “run of the mill” – four months in basic military training followed by 42 weeks in Officer Cadet School (OCS) at SAFTI Military Institute. I was commissioned an infantry officer on 29 March 1997 and subsequently completed two tours as a platoon commander – once in 1997-8 and again in 2001-2 after four years at university.

I volunteered to commence operationally-ready national service (ORNS) duties – colloquially referred to as “reservist” – that are usually two-weeks-long (up to 40 days) annually for a period of ten years. In 2004 I was posted to Headquarters Singapore Guards (HQ Guards). This is the formation tasked to “raise, train, and sustain” Guards battalions that specialise in heliborne and underslung operations. I was re-vocationalised as a Guards officer in 2006 upon completion of the Guards Conversion Course (GCC), and later completed both the Advanced Infantry Officers Course (AIOC) and the Battalion Tactics Course (BTC).

I believe that, in comparison with the US Army, the course content of GCC is comparable to the Air Assault Course while the syllabuses of the combined AIOC and BTC are similar to the Maneuver Captain’s Career Course. I have served ORNS for nine years and currently hold the rank of captain. Hopefully I’ll get called up for “my last rodeo” before I turn 50 (the cut off age for ORNS) and call it a day after ten years of ORNS duties.

You have interacted professionally with the U.S. Army multiple times and in multiple contexts, can you please share a bit about the types of experiences you have had with the U.S. Army?

This is an interesting question and upon closer reflection it would seem that my first ‘experience’ with the US Army was through “reel life” on television and through the pages of books. I had a dose of movies and documentaries with soldiers on horseback and manning forts in Antebellum United States, the respective dark blue and greyish uniforms of union and confederate armies, and shades of olive and green worn during WWII, Korea, and Vietnam. Then came the 1991 Gulf War, which was a 24-7 round-the-clock war on TV. It was school during the day and you watched the war in the evening. The iconic images of soldiers in desert camouflage uniform, the gas masks and protective suits, tanks, Apaches, and A-10s. Generals Powell and Schwarzkopf seemed to give endless press briefings, and who could forget the images of missiles hitting their targets. Then as I got older, I came across incidents like No Gun Ri in Korea, My Lai in Vietnam, and watched American personnel get dragged through the streets of Mogadishu during “Black Hawk Down”. So, there is a mental model of the immense and overwhelming strength of the US Army despite certain dark historical episodes and that it is, to borrow the term, on the whole “a force for good”.

My “real life” experiences with the US Army have been overwhelmingly positive. I must say that my experiences are certainly limited compared to career SAF officers, or those who have had the opportunity to be stationed in CONUS. Nevertheless, I appreciated most of the interactions that I have had with American military personnel. Three examples come to mind. First, I benefitted from then-major Greg Trnka who was an exchange instructor when I attended AIOC in 2005. Not just me but probably the whole course benefitted if one was willing to learn. Now he is retired Lt. Col. Trnka but always insisted after the course that he is simply “Greg”. Greg understood the doctrine, the tactics, and backed it up with the experience of company command and, if I recall correctly, he served on David Petraeus’ staff at the 101st airborne during the 2003 Iraq War. He showed genuine enthusiasm in teaching us Singaporean officers and injected a lot of practical and “common sense” considerations into our discussions beyond the “textbook solutions”. Having been in a warzone gave him “street cred”. Greg also went beyond just being an instructor. I remember that one of the regular commando officers sought his views on whether to attend the ranger course at Fort Benning or the special forces qualification course (SFQC) at Fort Bragg. Yes, to earn a prestigious tab. Greg opined that ranger was probably more beneficial at the platoon and company levels but since the officer was already in the midst, or even post-company command that SFQC would be better for the next phase of the career as battalion CO or senior staff appointments. The willingness to rationalise a position was something that stood out for me. My first interaction with an American army officer was a positive one.

Next, I spent six months in Afghanistan as a civilian researcher at the Centre for Conflict and Peace Studies in Kabul during the second half of 2006 and got to interact with several American personnel. I recall meeting Brigadier General Douglas Pritt who led CJTF Phoenix that was then anchored by units of the Oregon National Guard in training the Afghan National Army (ANA). General Pritt was very friendly, respectful, and had no illusions of the immense task that he and his brigade had in front of them. I think his command sergeant major had the ranger tab and was a school teacher in civilian life. We joked that teaching in America was that challenging. Jokes aside I was impressed with the national guardsmen leaving their civilian occupations and stepping into their military roles in Afghanistan. It was only natural to make comparisons with the Singapore Army and wonder about the possibilities of one day doing the same. There was no chance. I am also grateful to two US army officers from the J5 branch at Camp Eggers who helped me with a paper I wrote on the ANA and later published with Military Review. The domestic flights by NATO partners allowed interactions with a few US Army reservists. One was a chaplain and his assistant who were visiting trainers embedded with the ANA. Another was an individual mobilization augmentee who was a vehicle mechanic and a veteran of the 1991 Gulf War. You get to hear their stories, what they did in civilian life, and understand how their tours in their respective MOS are like. I really appreciated their candour, concerns, and circumspection.

Finally, I got the opportunity to participate in Exercise Cobra Gold in Thailand in 2010. Here I met retired Lieutenant General Thomas Montgomery who was a mentor and advisor to the UN portion of the exercise given his experiences as deputy commander of United Nations Forces in Somalia. General Montgomery was a Vietnam veteran and Cold War warrior and this opened up a glimpse of a different time past. Things like exercise REFORGER, facing off against Soviet-bloc forces across the Iron Curtain. What struck me was the general’s emphasis on unity within a multi-national setting. He was very clear on the important roles played by the Pakistani and Malaysian peacekeepers toward the conclusion of Operation Gothic Serpent.

I must say that my (very limited) experiences with the US Army have been positive. The individuals mentioned have been nothing but respectful and wonderful ambassadors for both uniform and country. Of course, the same applies to you, Dan. We met at the Rajaratnam School in Singapore after you graduated from West Point near the top of your class. I think of you whenever I hear anyone say that Americans are insular. My response is always “no, that generalisation is incorrect.”

That’s very kind Samuel, thank you! Now transitioning a bit, when we think about the Singaporean military, what has its relationship been with the U.S. Army? How has this relationship changed significantly over the past 61 years since Singapore’s independence?

The relationship between the armed forces of Singapore and the United States is based on mutual respect and has moved from strength to strength. Our two countries completed the artillery Exercise Daring Warrior at Fort Sill, and the air-ground Exercise Green Flag West at Nellis Air Force Base in September. Singapore’s Chief of Defence Force (CDF) met the CJCS in Washington in October. These activities are at the tip of the proverbial iceberg and the US Army’s role is perhaps second only to the United States Air Force in terms of impact on Singapore’s military development. The relationship is built on trust, respect, and has been mutually beneficial. The US Army sets a high benchmark for military development and capabilities in terms of personnel and assets. The Singapore army is a modern, trustworthy, and operationally-ready partner. Land forces from the US and Singapore that have participated in bilateral exercises such as Tiger Balm (since 1981), Valiant Mark (since 1991), and multilateral exercises such as Cobra Gold (since 2000) and Super Garuda Shield (since 2022) can attest to this.

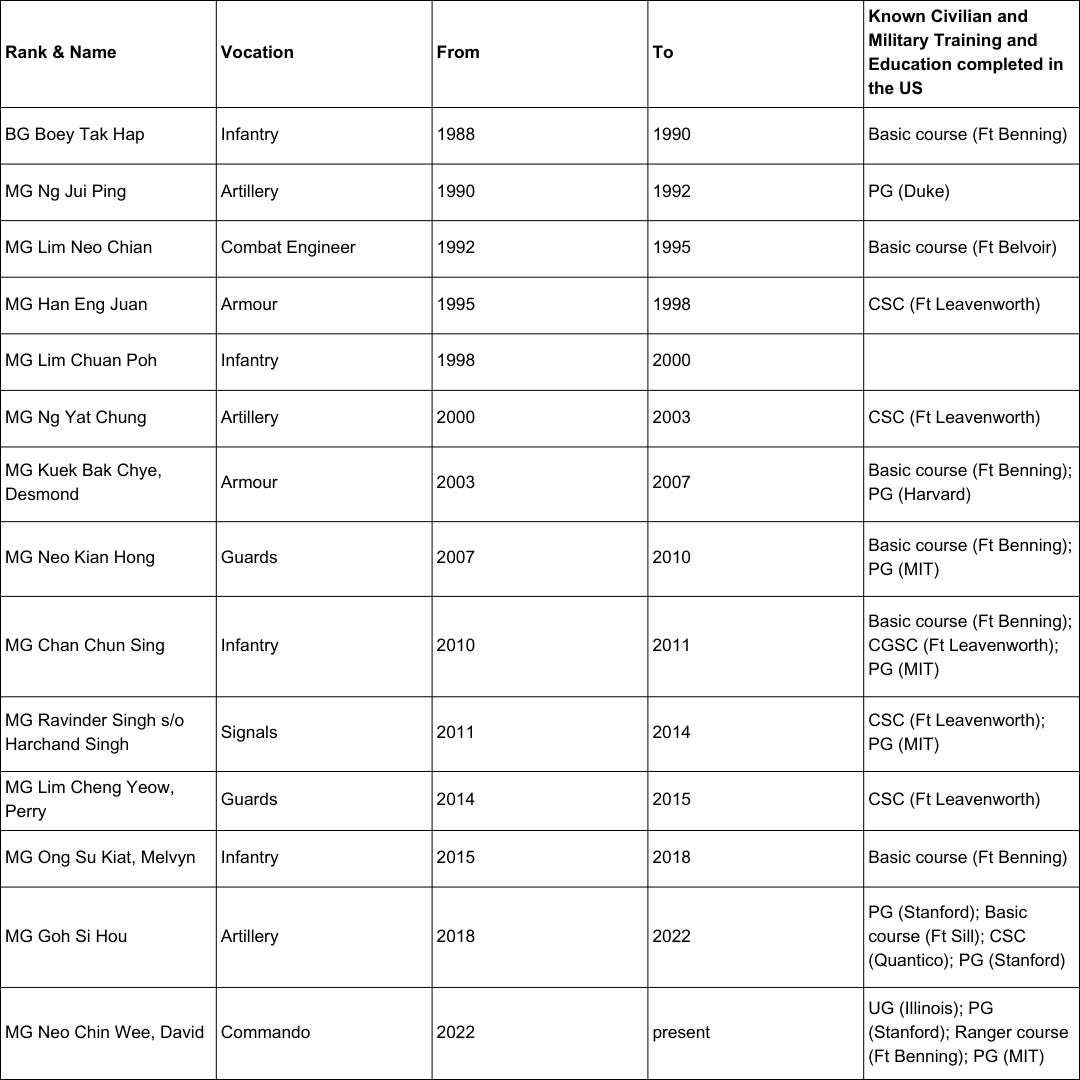

The US Army has played an important role in the Singapore Army’s growth from a mere two battalions – the 1st and 2nd battalions, Singapore Infantry Regiment (1 & 2 SIR) – at independence in 1965 to a modern six-division war machine today. Singapore was, and still is, under no illusions that the US Army cannot be copied wholesale. Hence it is necessary to learn, to purchase, and to assimilate where applicable. In the early days the Singapore military was dependent mostly on the United Kingdom and Israel, both of which left indelible marks to this day. The US Army came onboard slowly through logistics and in the days since American military equipment, and training and education have become ubiquitous. I am sure audiences will be familiar with items such as the AR-15, M-16, M203, 105 mm recoilless rifle, M113, C-130, UH-1H, AH-64D, CH-47, and HIMARS in service with the Singapore Army. As for expertise one could describe the training and education provided by the US Army as “indispensable”. Access to vast training areas is valuable because it allows Singapore to test its power projection capabilities, to validate warfighting concepts, and to experience stressors on personnel and platforms. The US Army is also a leading source of combat experience and associated innovation. Finally, the United States is the premier location for the development of Singapore’s military leaders in terms of undergraduate (UG) and postgraduate (PG) education, and basic and intermediate military courses. Take for example the officers who have held the title of Chief of Army (see Table 1).

Table 1: Chiefs of the Singapore Army and attendance at formal American civilian and military courses/programs (note: BG = Brigadier General; MG = Major General)

Another example is to consider your fellow members of the Long Gray Line (West Point graduates) from Singapore such as:

Brigadier-General Yew Chee Leung (USMA Class of 2000), former Director Military Security and incumbent Deputy Secretary (Technology) / Future Systems and Technology Architect, Ministry of Defence.

Colonel Alvin Tjioe Jin Kiat (2005), former Commander Officer Cadet School (OCS) and incumbent Commander Personnel Command.

Colonel Alex Wang Jin Rong (2005), former Chief Supply Officer and incumbent Head SAF Centre of Leadership Development, SAFTI Military Institute.

Colonel Fan Mun Poh (2006), former Commander 3rd Singapore Infantry Brigade.

There are other ways to illustrate the impact of American training and education on the Singapore Army but I am sure that the audience catches the drift – that you will find a significant American imprint on the Singapore Army.

Thank you for taking us through that history. I overlapped with Alex Wang Jin Rong and Fan Mun Poh at West Point and remember the Singaporean cadets for their professionalism and competency.

Now to close this section out, drawing on both your personal experience and your professional expertise as a scholar and practitioner of national security, what do you think have been the strengths of the relationship between the U.S. Army and the Singaporean military? And where do you think it either could have been improved in the past or where it could be improved going forward?

The willingness to engage, to learn, to make things work, and mutual respect have been positives for the relationship between both armies. I say this because there are reasons for the relationship not to work. The US Army is part of a global juggernaut that is the US military – I don’t think any other country divides up the globe into combatant commands and has the power projection capabilities to back it up. The Singapore Army, on the other hand, is a conscript-centric outfit with limited scope to operate beyond the direct defence of Singapore. The largest land combat ‘unit’ from the Singapore Army deployed overseas for operations was a reinforced rifle company of 160 peacekeepers to Timor-Leste in 2002. So, a positive working relationship between both armies is reflective of the (political) relationship between Singapore and Washington – you could describe it as ‘good friends without obligations’. We’re not allies and this is a good thing. Singapore takes its own defence seriously and is not in the habit of free-riding when it comes to defence. The rationale is not to cede any measure of sovereignty by falling into the orbit of a stronger power through the protective umbrella afforded by an alliance. Singapore is not going to fight someone else’s war(s) and does not take peace for granted because no one is obligated to come to its rescue in times of armed conflict.

Improving this relationship between the two armies really depends on the goal. Right now, the ‘temperature’ seems right – at least from official news releases and social media feeds from the Singapore Army – with exercises, training courses, operational weapon platforms, high-level visits, and the seemingly ubiquitous reaffirmation of “excellent bilateral defence relationship” at every juncture. I do not think both armies will ever achieve interoperability to the point of established joint force HQs. There is no need for one. We are not allies and we have limited history. Singaporeans are not the British, Canadians, Australians, Kiwis, or Koreans so it is very unlikely that a Singaporean army colonel or brigadier-general will serve as Deputy Commanding General at the division (or higher levels) of the US Army. Perhaps a possible and realistic improvement is to have exchange instructors on milestone courses. A cross-pollination of ideas and cultures. I am thinking of three US Army officers seconded to SAFTI Military Institute at Officer Cadet School, the Army Officers Advanced Schools, and the Goh Keng Swee Command and Staff College. In return three Singapore Army officers are seconded at one each to USMA West Point, the US Army Maneuver Center of Excellence, and CGSC at Leavenworth. We’re talking about a captain, a major, and a lieutenant colonel. Provide the correct career incentives and I do not see why such an amplifier in terms of defence diplomacy cannot proceed. It can be a win-win situation for both armies.

U.S. and Singaporean soldiers run together near Marina Bay, Singapore. Source: DVIDS.

That’s really helpful, Samuel. I appreciate how you characterize both the relationship between the US and Singapore and Singapore’s approach to its defense. I’d like to stay on this second theme for an additional question. You wrote a book, Aristocracy of Armed Talent: The Military Elite in Singapore, that offers the holistic, sociological type of analysis pioneered by scholars such as Morris Janowitz. I don’t think this was part of your research, but did your work on the book uncover any significant similarities and/or differences between the military elite in Singapore and the military elite in the U.S.? Is there anything more about your book you’d like to share?

There are certainly similarities and differences between the military elites and indeed the armies in both countries. For simplicity let us assume that ‘military elites’ are general rank officers. Let me also provide some background for your audience. Military elites in the Singapore Army consist of a number of Brigadier-Generals (one-star), and one Major-General (two-star) who is the Chief of Army. The CDF – who is the equivalent of CJCS and Unified Combatant Commander in your military – is a three-star (Lieutenant-General or Vice-Admiral). An army colonel is usually promoted to one-star while leading as a Division Commander. After this there are several billets at the army (operations, training and doctrine, Chief of Staff – General Staff) and joint levels (joint operations, commandant SAFTI Military Institute, Chief of Staff – Joint Staff). The Singapore Army is a lot smaller and the hierarchy a lot flatter compared to the US Army. There are no corps or field armies, no army aviation (all rotary and fixed winged aircraft fall under the air force), and no equivalent of a national guard.

There are also several points to place in context regarding the career of a regular Singapore Army officer:

A university degree is not a pre-requisite for an officer’s commission.

The mandatory age of retirement for officers is 50.

The majority of postings are at military installations on the main island of Singapore, which measures some 49km (east-west) by 28km (north-south). The total area including outlying islands is around 735 square kilometres (284 square miles). That is smaller than the combined size of Forts Campbell and Drum. Regular/career personnel live off base when not training or on duty. As such, it is rare for the families of army officers to move because of a posting perhaps with the exception of those stationed at diplomatic missions abroad.

The Singapore Army is a citizen’s army. Units are usually manned by conscripts serving (currently) 24 months of fulltime national service, or operationally-ready national servicemen (ORNSmen or ‘reservists’) recalled for annual in-camp (refresher) training. There are all-regular units such as the Army Deployment Force, the Special Operations Force, and other classified units. ORNSmen have climbed the ranks to commanded battalions as majors and lieutenant colonels, and brigades as senior lieutenant colonels and colonels. The pinnacle appointment to date has been Division Chief of Staff.

There is the military domain expert scheme (MDES) that runs in parallel to the officer corps. This scheme is designed to retain expertise in certain areas such as intelligence, engineering, and medicine. The mandatory retirement age for MDES personnel is 60. The highest MDES rank of Military Expert 8 is equivalent to Brigadier-General.

You would have already noticed similarities and differences from the paragraph above and there are several others to highlight. There are similarities in rank and force structure. The Singapore Army’s officer rank structure mirrors the US Army from O-1 to O-9 with the exception of senior lieutenant colonel between O-5 and O-6. In terms of force structure, Singaporean officers lead at platoon, company, battalion, brigade, and division-levels. The principal staff officers include manpower (S1/G1), intelligence (S2/G2), operations (S3/G3), logistics (S4/G4), plans (G5), and training (G6). The vocations – what you would call the MOS – are roughly similar and divided up into combat (infantry, armour, guards, commando), combat support (artillery, combat engineers, intelligence, signals), and combat service support (medical, engineering, logistics). Officers in Singapore are judged on performance and potential that in turn determine their postings and promotion prospects. I believe that this is much the same in the US Army with certain exceptions such as a premium placed on combat experience, and the ‘joint duty’ requirements stipulated by the Goldwater-Nichols Act. Military elites in both countries are those who rise to the top by remaining on active duty, proving themselves, getting noticed, avoiding career ending situations (death, injury, discipline), and probably an element of luck. I can go into similarities with regards to pixelised uniforms, the use of berets, and heraldry but that is superficial. Coincidentally, there is a ‘Ranger’ tab for those who complete the SAF Ranger Course, and graduates of the SAF Special Forces Qualification Course also wear a ‘Special Forces’ tab.

There are five differences to note. First, the US Army has three commissioning sources: ROTC, West Point, OCS. The Singapore Army has one, which is the Officer Cadet Course run by Officer Cadet School at SAFTI Military Institute. The closest comparison is probably the commissioning course at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, in the United Kingdom. Second, the career duration of Singapore’s army general is around 20 to 25 years after completion of tertiary education. This means shorter time in appointments, fewer appointments held, and relative youth in relation to the US Army. Third, not all officers are career managed equally. Recipients of the SAF Scholarship are specially groomed for senior positions and afforded every opportunity up to battalion command to succeed (or fail). One in three makes it to brigadier-general on average, and SAF scholars account for almost all of the major-generals and lieutenant-generals in SAF history. That said, the majority of brigadier-generals are not SAF scholars. You can say that Singapore’s top brass is where realised potential and demonstrated talent meet. Fourth, Singapore’s military elites are comparably short on operational (and certainly combat) experience leading some local armchair critics to label them ‘paper generals’. This is a misnomer. Singaporean generals have led humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operations, and served as deputy and force commander on UN peacekeeping missions. The fact that the Singapore Army has not fired a shot in anger is a reflection of never failing in its mission to deter aggression, and the lack of expeditionary opportunities due to limitations of where a conscript-centric force can be deployed and employed. The final difference of note is public access to in-depth stories of those who lead at the highest levels of the armed forces. Aristocracy of Armed Talent was motivated in part after I read The Fourth Star by David Cloud and Greg Jaffe. It is not surprising that I have greater familiarity with the stories of officers like Colin Powell, Eric Shinseki, Peter Pace (USMC), and Martin Dempsey than I do with most Singapore Army generals. I put this down to cultural norms. In America, ‘you need to know’. In Singapore, ‘you do not need to know’.

Having some personal experience with the Singaporean military, I definitely would vouch for its professionalism and competence; and as you artfully noted, its lack of comparable “combat” experience is overwhelmingly due to Singapore succeeding with its military and national defense strategies.

Now, to close out the interview, I’d love to get your thoughts on why people outside of the military should try to learn about the military: why should a Singaporean or American citizen see it as important to establish more than a cursory connection to the military?

The academic answer is that the military is a tool of statecraft and its use is a reflection of policy. Citizens should take an interest in how the state behaves in their name especially when force is used, lives are taken, and lives are lost. This is essential for the ‘health’ of democracies and both the United States and Singapore are democracies. There are those who will disagree. We can go into how the countries differ in politics (e.g. ‘liberal’ v ‘guided’, ‘presidential’ v ‘parliamentary’, contents of the constitution, mandatory v voluntary voting etc) but the basic premise is that Singaporeans and Americans have a choice at periodic ‘free and fair’ elections.

In practical terms, let me proffer ‘rights’ and ‘duty’ as two simple reasons – different sides of the same coin – for why a citizen should bother to learn about their military. Americans and Singaporeans are both familiar with their ‘rights’ (and ‘entitlements’) as stated in the respective constitutions, and through prevailing laws and policies. Freedom of religion, speech, and assembly are similar. The right to bear arms is not. We often hear and speak of rights. “It is my right to this, to that.” It is equally important to consider the preservation of those rights. This is where ‘duty’ comes into play. The duty to preserve those rights is not something that is instinctive in times of peace, of comfort, and on full stomachs. There are various roles in society that serve to preserve our rights. Each is different and demands differently. As for the military, I cannot help but recall the words of Father Dennis Edward O’Brien (1923-2002), one of your ‘greatest generation’ who served as a marine during WWII and then a Catholic priest for almost half a century, who wrote:

“It is the soldier, not the reporter, who has given us the freedom of the press. It is the soldier, not the poet, who has given us freedom of speech. It is the soldier, not the campus organizer, who has given us the freedom to demonstrate. It is the soldier, who salutes the flag, who serves under the flag, and whose coffin is draped by the flag who allows the protestor to burn the flag.”

That to me is reason enough to go beyond a superficial understanding of the military.

There are avenues in both America and Singapore for any citizen to establish more than a cursory connection to the military. You have Veterans Day. You honour those who serve(d) at various social events. Army Day, Twilight Tattoo, memorials, museums, and websites. There are countless books on the US military. You can easily reach out to a recruiter and/or a veteran in person. US Army Recruitment Command tells me that “[t]here are approximately 10,900 Soldier and civilian recruiters working out of more than 1,400 recruiting stations across America and overseas.” Pew Research says that 6% of America’s adult population served. An American citizen is spoilt for choice should they choose to make a deeper connection with the military.

We have a citizen military in Singapore. Sons are conscripted upon reaching the statutory age of 18, or on completion of their studies. Daughters are joining the military in increasing numbers. So, in some sense, it is in the interest of every family to know a bit about the Singapore Armed Forces. The government also takes great lengths to engage society through open days at military installations with static displays, a dedicated ‘national education’ program with a strong emphasis on the need for citizens to be committed to defence, military visits to secondary schools and polytechnics (technical schools), and a division commander / formation chief from the army is always tasked with organising the annual national day parade on August 9. We are relatively light on Singapore military literature, and official websites are rather pedestrian. That said, more than one million men have completed their national service so Singapore is also not short on ‘conscript veterans’ per se. A Singaporean citizen is similarly spoilt for choice should they choose to make a deeper connection with the military.

Samuel, thank you so much for contributing your time, thoughts, and expertise to the Army 250 community.

Singaporean soldiers at the U.S. National Training Center, Fort Irwin, California. Source: DVIDS.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview are those of the interviewee and do not reflect the official views or positions of the Ministry of Defence, the Singapore Armed Forces, or other affiliated entities of the Government of Singapore.

Additional Resources:

The U.S. Army and the Singaporean Military conducted the 43rd annual Exercise Tiger Balm last year. Learn more here.

You can learn more about the Singaporean military at the Ministry of Defence’s website here.

You can learn more about the relationship between the U.S. and Singapore on the website of the U.S. Embassy Singapore here.

You can learn more about Nanyang Technological University, which I attended as a young officer and where Samuel and I met, here.

Be Part of Army 250

If you’d like to write a newsletter post, share an educational resource about the Army, or lift up an opportunity for people to connect with the Army (e.g., an event, story, etc.), please contact Dan (dan@army250.us).

This is great, Dan. We always had a few Singaporeans joining our early training to give their Frogmen some expertise. Interesting from the perspective above.